Hannah on an Ancient Hilltop – A Tale for the New Year

Hannah on an Ancient Hilltop – A Tale for the New Year

On the Jewish New Year, the sacred readings reverberate with the triumphs of the vulnerable and the powerless. On Rosh Hashanah we remember that Sarah’s longing for a child was requited (Gen. 21) – and Hannah’s humiliation came to an end when her son Samuel was conceived (1 Sam. 1–2). In her thanksgiving song, Hannah compares that miracle to no less than victory over enemies, evil, death and injustice. The Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 11a) also says this was the time of year that the hopes of another barren woman of the Bible were fulfilled – Rachel (Gen. 30:1).

Hannah and Eli the priest. Engraving by German painter Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1764–1841). Wikimedia Commons.

There’s even part of the sacred liturgy of Rosh Hashanah that’s couched in terms of birth: Congregations around the world chant the hymn Hayom Harat Olam, which means (freely translated) “this day is pregnant with eternity,” reflecting the belief that Rosh Hashanah is the world’s birthday.

A few weeks ago, I asked my husband Arik if he wanted to take a little archaeology-themed drive to a rocky hilltop not far from our home that I had read might be the burial place of Hannah. I didn’t realize until I stood among the ruins there that a Rosh Hashanah message was hidden among them.

Hannah times three

It dawned on me there that we now have three places to remember Hannah in the Holy Land. The first, of course, is where Scripture says Hannah prayed for a child – Shiloh, next to which an elaborate visitor center now stands. The second is Ein Karem, at the Church of the Visitation – where Elizabeth and Mary met when both were pregnant. That’s the perfect place to read Mary’s paean of praise, the Magnificat, which she traditionally uttered there. Hannah comes into our midst naturally as we compare the Magnificat to Hannah’s prayer.

And now a third place – this hill, called Burj el-Haniyah in Arabic, and Horvat Hani in Hebrew. It’s marked by the remnants of an ancient convent excavated some 18 years ago by a team led by Uzi Dahari and Yehiel Zellinger. The intersection of an unpaved forest road with the path to Horvat Hani, on a rocky mound in the western Bethel foothills, is almost invisible. But what I would like to see here very clearly is an intersection of three traditions remembering a remarkable woman of Scripture.

Wall of the convent, visible from the dirt road that passes Hurvat Hani, “Hannah’s Ruin.” Miriam Feinberg Vamosh.

Archaeologists tell us that the complex that once stood here contained a church, crypt, convent, tower, seclusion cells for nuns (which, by the way, could be locked from the inside, which is not the case in men’s monasteries) a kitchen, pilgrims’ accommodations, dining room, courtyard, olive presses, a winepress, storage cave and cisterns! Human bones were also unearthed. The bones were only of infants, children and women, whereas archaeologists say they normally find at least some male skeletal remains in such a mix. Hence, they conclude, this was a convent.

Artist’s rendering of the church and convent over Hannah’s putative burial place. Courtesy of Uzi Dahari.

When I was there last month, almost everything was overgrown but the church apse, and I barely caught a glimpse of the cave openings, choked with thick, dry vegetation. After my time on the hilltop, when I hopped back into the van where Arik was patiently waiting, the first thing I said was: “I forgot my cellphone in the van.” “I know,” he responded laconically. We admitted that we both realized I could have ended up at the bottom of one of those ancient caves…Not the kind of drama I had come to invoke!

People may have started coming here to pay homage when only an arcosolium (arched-ceiling tomb) stood on the hill, built in the second or third century CE, and containing, the archaeologists say, a number of female skeletons. But pilgrims really started streaming in apparently in the fifth century when the convent was first built, with the tomb now in a place of honor under the church apse. And even after the site was abandoned, girls and women, probably Muslims from surrounding villages, continued to be buried there. But who was the revered lady in the tomb? Part of the Arabic name of the site, Haniyah, has led scholars to conclude she was Hannah.

But which Hannah?

Among the scriptural women named Hannah, or Anna, is Jesus’ grandmother and the Temple-residing prophetess of the New Testament. And then – and perhaps most intriguing – there’s Samuel’s mother. That Hannah, the Bible says, was from Ramatayim-Tzofim (1 Sam. 1:1), and the Church father Eusebius, whose lead pilgrims would have followed, identified Ramatayim-Tzofim as as a place he called Remphis, east of the pilgrimage magnet of Lod (Lydda). Following the thread of name-related clues, we find that Remphis apparently morphed into the present day village called Rentis, which can still be seen from the ruined church walls.

Apse of the church at Horvat Hani, “Hannah’s Ruin,” looking east toward Rentis. Miriam Feinberg Vamosh.

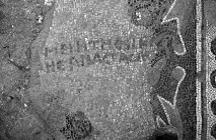

One of the three mosaic inscriptions in Greek unearthed at the site, in fact, right in the church, reads: “Remember O Lord, Anasia, “the abbess” (or “the most pious”).

Inscription honoring “Anasia, the abbess,” or “the most pious.” Courtesy of Uzi Dahari.

The story of Hannah has many lessons that cross the boundaries of faith and culture. One was taught by the ancient rabbinic sages: Hannah’s experience shows the power of prayer as it pours from the heart. (And that’s knowing how important structure is to Jewish prayer services.) And moving from form to essence – Hannah’s prayer, as well as the Magnificat, speak volumes about the power of change, and the possibility of an end to suffering symbolized by that ultimate transformative experience, childbirth.

May Rosh Hashannah be a time of rebirth and new beginnings for us all.

Thanks to Dr. Uzi Dahari for his assistance with information and illustrations.

Hurvat Hani is an off-the-beaten track ruin in the Samarian foothills northeast of Shoham and northeast of road 444. It appears by that name on the 1:50,000 map of Israel (available in Hebrew only). There are no English signs at the site. Colleagues and others interested in reaching Hurvat Hani can contact me for more specific directions.

Want to know more?

Bolton-Fasman, J. 2016. Hannah’s Prayer: A Rosh Hashannah Story. https://www.jewishboston.com/hannahs-prayer-a-rosh-hashanah-story/

Cook, J.E. 1999. Hannah’s Desire, God’s Design: Early Interpretations of the Story of Hannah (Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 282).

Cohn, G.H. 2000. A Prayer for Rising Above the Routine. https://www.biu.ac.il/JH/Parasha/eng/rosh/coh.html) (a ccessed Aug. 22 2018).

Dahari, U. and Zelinger,Y., with contributions by L. di Segni, Y. Nagar and E. Klein. 2016. The Excavation at Ḥorvat Ḥani – Final Report and a Survey on Nuns and Nunneries in Israel. In: Knowledge and Wisdom. Archaeological and Historical Essays in Honour of Leah Di Segni (Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Collectio Maior 54).