A Thousand to One on Ancient Ramparts: Better Bet on Wisdom

A Thousand to One on Ancient Ramparts: Better Bet on Wisdom

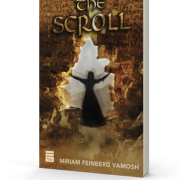

The wise woman of Abel is assuming her rightful major role in our understanding of biblical women more than ever these days. This is in great measure thanks to the ongoing excavations in her hometown, Abel Beth Maacah, co-directed by Nava Panitz-Cohen and Robert Mullins, which this summer produced another bumper crop of exciting finds. And, full disclosure: My own renewed fascination with the site is because of the part the wise woman plays in the new novel I’m writing.

The story of the wise woman of Abel emerges in Scripture from an intersection between geography and dysfunctional family ties, and has been filled out by the untamed imagination of the ancient Jewish sages. First: the geography: Tel Abel Beth Maacah is a large mound about three quarters of a mile south of the farming and vacation town of Metulla, near Israel’s northern border with Lebanon. In ancient times the city straddled a major road between Damascus and the northern Mediterranean coast.

As for the dysfunctional family aspect, I’ll start with something familiar: Absalom rebels against David, ostensibly to avenge his sister Tamar’s rape by their half-brother Amnon. (Why ostensibly? Mu new novel will reveal what I believe really happened.). A tumble of events and barely pronounceable names then shoots by at breakneck speed, leaving us wondering…Wait…what? Who? These are followed by another familiar tale – Absalom’s death. And after that…casual readers might interpret the settling of accounts that follows as closure for David.

But then in the blink of an eye, we’re told that the northern tribes have begun to squabble with David. A clash of words, as Robert Alter puts it, leads to a clash of swords. The men of Israel break away from Judah, sparking more civil war, starring David’s longtime, brook-no-opposition commander Joab, the rebel Sheba son of Bichri and our wise woman (2 Sam. 20: 1–15) .

The people of Abel allow Sheba to hole up there for some reason. According to a 1961 article by Prof. Benjamin Mazar, David had made Abel a vassal of his. So might the Abelites have harbored Sheba out of revenge, despite the wise woman’s claim that they were “peaceable and faithful in Israel” (2 Sam. 20:19)?

Be that as it may, out of nowhere, up pops an isha hachama, a wise woman, on the ramparts. Her brief statements to Joab have been picked through with a fine-toothed comb by the ancient Jewish sages, particularly in two sources, Genesis Rabbah and Ecclesiastes Rabbah.

Ecclesiastes Rabbah explores the exchange between the wise woman and Joab. According to Scripture, she asks him: “Art thou Joab?” Not the most obvious way to jumpstart ceasefire talks, so, say the ancient commentators, there was more to it. Scholar Tamar Kadari points out that the sages believed the wise woman was taking the Judahite general to task: “Your name is Joab [yo-av]? Your name does not suit you! It teaches that you are a father [av] to Israel, yet you kill them” (Gen. Rabbah 94:9).

Next, on the face of it, comes some self-serving PR: “They were wont to speak in old time, saying: They shall surely ask counsel at Abel; and so they ended the matter” (2 Sam. 20:18). But according to the sages, “so they ended the matter,” really meant “that was the end of it,” and “it”, they conjectured, was the wisdom of the Torah, which, when it came to Joab, had “ended.” Why? Because Joab did not follow Deut. 20:10: “When you approach a town to attack it, you shall offer it terms of peace” (Eccles. Rabbah 9, 18, 2). In other words, talk before your shoot.

One for a thousand: a fair trade?

How did the wise woman get the people of the city to agree to execute Sheba and give Joab his head (2 Sam. 20:22)? The Bible doesn’t say, except that she acted “in her wisdom.” But the sages come to the rescue once again: They pictured her shuttling between the citizenry and Joab, each time telling them that Joab would accept a smaller number of people killed to save their town, and finally, that he really only wanted one particular man – Sheba. The wise woman, it was said ,saved “1,000 lives” by sacrificing one. This imaginary negotiation echoes Abraham’s failed attempts to save Sodom, Kadari notes.

Sacrificing one individual for the good of the many has for centuries fostered multifaceted debate. As scintillating as such debate may be, if only the words of Ecclesiastes 9:18 – which the ancients said were embodied in the wise woman of Abel – would guide our leaders, the world would be a different place: “Wisdom is more valuable than weapons of war. ”

Want to know more?

Alter, Robert. 1999. The David Story: A Translation with Commentary of 1 and 2 Samuel. New York.

Kadari, Tamar. “Wise Woman of Abel-beth-maacah: Midrash and Aggadah.” Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 27 February 2009. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/wise-woman-of-abel-beth-maacah-midrash-and-aggadah (viewed on July 22, 2019) .

Mazar, B. “Geshur and Maacah.” Journal of Biblical Literature 80:1 (March 1961): 16–28.