Chanel No. 5 A.D.

Chanel No. 5 A.D.

When I brought the young woman I called Rebecca in The Scroll to the Dead Sea oasis of Ein Gedi, I wanted to make her fate spring from the pages. And thanks to archaeologists and historians, I believe I found the perfect backdrop – the balsam industry.

Balsam was a mysterious ancient plant whose sap exuded from its shrubs “like tears”* and whose scent and salve sold for double its weight in silver**

In a strange twist of history, the plant the ancients knew as commiphora opobalsamum became extinct. But a subspecies, commiphora gileadensis, is now being raised in the Erlich family orchard in the Dead Sea Valley in the hopes of producing the precious substance once again in our region!

Balsam production factory, artist’s rendering (Daily Life at the Time of Jesus, p. 77, courtesy of Palphot)

Fascination with balsam goes back millennia, and the discoveries don’t stop. Recently, a two millennia-old water system was unearthed in a new Israel Antiquities Authority excavation of a site first found in the 1960s near Ein Bokek near the Dead Sea.

Balsam production pool at En Bokek (photo: Dr. Tsvika Tsuk, Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

The English Bible translates the Hebrew name – afarsimon – as “balm” (Genesis 37:25). For Jeremiah, afarsimon symbolized hopelessness: “There is no balm in Gilead.” The opposite message is conveyed in the traditional spiritual “There is a Balm in Gilead.”

Artist’s rendering of what may be a balsam factory at Enot Tsukim on the Dead Sea (photo courtesy of Dr. Tsvika Tsuk, Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

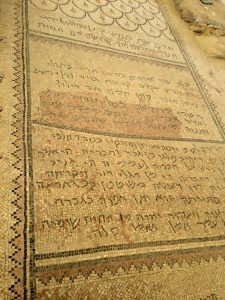

Scent and the City

I recall a story about a man with a sign on his desk that said: “my job is so secret even I don’t know what I’m doing.” The people of Ein Gedi knew what they were doing alright (making balsam products); they just didn’t want anybody else to know. They kept their secret so well that nobody actually does. At Ein Gedi National Park, the mosaic floor of the ancient synagogue has an inscription cursing anyone who revealed “the secret of the town” – “He whose eyes range through the whole earth and who sees hidden things will set his face on that man and on his seed and will uproot him from under the heavens.”

Inscription on the mosaic floor of the Ein Gedi synagogue containing the “curse of the secret” (photo courtesy of Dr. Tsvika Tsuk, Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

I hope that in The Scroll, I’m able to give readers even a whiff of what I imagine was the ancient aroma’s allure, so powerful that robbers in Sodom could sniff it out in the homes of the wealthy and steal it at night (Talmud, Sanhedrin 109a). As for the plant-to-perfume process, I believe I moved my plot to a peak by showing how some scholars say the sap was made into the costly unguent, and the branches boiled in tubs and mixed with olive oil for a less expensive product.

At Arugot Fort, near Ein Gedi, a fourth-century AD tower preserved to a height of 18 ft (and probably originally three stories high), with thick walls and a rolling stone to seal the door, was probably a balsam factory. It served as inspiration for scenes in The Scroll. (Photo: Dr. Tsvika Tsuk, Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

But balsam in The Scroll is more than a plot device. Just as ancient balsam production began with the “tears” of the sap and ended (hopefully) with “reaping in gladness” – those very words from Psalm 126:5 encapsulate hope, across the generations, in the story I tell.

Want to know more?

“Three Chapters of Balsamon History,” by the Erlich family. www.jerichovalley.com

“A Balsam Factory” in: Daily Life at the Time of Jesus, by Miriam Feinberg Vamosh (Palphot) p. 77.

“The Balm of Gilead.” Biblical Archaeological Review. October 1996, pp. 18–20.

“Balsam Perfume” – the ancient juglet in the Israel Museum. http://www.imj.org.il/exhibitions/2013/Herod/en/balsam.html

Qumran in Context, Yizhar Hirschfeld (Hendrickson 2004) pp. 207–209, 216–220, and see index for many more references to balsam. (The late Prof. Hirschfeld, scientific adviser on some of my books, told me he hoped that original balsam plant material could still be found at Ein Gedi and that some day a finished product would be produced jointly by all the countries in our region.)

*Josephus, The Jewish War 1, 1, 6.

**Pliny, Natural History 12, 54.