Sukkot – A Season for All Peoples – and a Time to Think Out of the Box

Sukkot – A Season for All Peoples – and a Time to Think Out of the Box

As a tour educator, when I have the privilege of explaining about our holiday of Sukkot to people of other faiths and cultures on guided tours of Israel, I sometimes like to call the holiday “the Jewish Thanksgiving” to draw attention to one of its facets – giving thanks to the Almighty for the bounty of the fall harvest. In our case the harvest does not include the plump orange pumpkins or shiny red apples of my childhood in the northeastern United States. Instead, here in the land of the Bible we give thanks for the harvest of the biblical fruits of the season (Exod. 23:16), such as grapes and olives, and for the strength for the hard work (in Bible days) of processing them into edible products.

Sweet grapes from our burgeoning vine, brought as a welcome-to-the-region gift and planted 28 years ago or so when we moved into our house, by Abu Ghazi, the “patriarch” of the workers from the neighboring Palestinian village who built our home. It was a different time.

But like all biblical holidays, Sukkot has more than one layer of meaning. It commemorates the Israelites’ sojourn in flimsy “booths” put up during the wandering in Sinai (Lev. 42:53). For more about today’s tabernacles see my Sukkot holiday blog, “Turning Ourselves Inside Out.” In biblical times celebrants were commanded to take “choice fruits from the trees, and palm fronds, leafy branches and willows (Lev. 23:40) and wave them before the altar in the Temple. These plants are known as the Four Species, and today worshippers commemorate the Temple service by waving and shaking them at certain moments during morning prayers in the synagogue or at home. Yom Kippur, which we recently marked, is often considered a very personal kind of commemoration. But like Sukkot, it has universal aspects too. On Yom Kippur we recite the words “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples (Isa. 56:7). The Bible reading for the Yom Kippur afternoon service is the Book of Jonah, whose final verses reflect God’s loving concern for all peoples of the world.

As for Sukkot – we are taught that one universal aspect of Sukkot is the fact that the total number of sacrifices offered during Sukkot was 70 – the biblical number of all the world’s nations. If you’ve had the privilege of being in Jerusalem on Sukkot, one of the three pilgrimage holidays, you certainly sensed the Holy City as a true microcosm of all peoples.

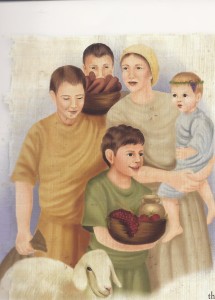

An ancient family on Sukkot pilgrimage to Jerusalem, from my book Teach it to Your Children: How Kids Lived in Bible Days (drawing by Mira Hass)

In fact, the universal and the personal are never very far apart in our tradition. The shape of each of the Four Species reminded the ancient Jewish sages of different aspects of the human body. The lulav (the straight, closed palm frond) – the spine; the oval etrog (citron) – the heart; the small leaf of the myrtle bush – the eyes, and the longer leaf of the willow – the mouth. Holding the Four Species together and shaking them in every direction, the sages said, was a way of “enacting” Psalm 35:10 – praising God as the source of justice: “All my bones shall say: ‘Lord, who is like unto Thee, who deliverest the poor from him that is too strong for him, yea, the poor and the needy from him that spoileth him?’” For added inspiration, check out the connection of this thought to Paul’s counsel to the Romans (12:2). But for a broader, society-oriented take, I thank the rabbi of my hometown of Har Adar, Rabbi Naftali Rothenberg, for his remarks on the Four Species in an article published recently on Ynet. His thoughts, particularly about the etrog, actually do not echo my own, but they did lead me back to thinking about the etrog as a symbol of striving for a more perfect world. This ideal is woven into countless verses in the Bible; for example, one of my favorites is Jeremiah 22:3: “Execute ye justice and righteousness, and deliver the spoiled out of the hand of the oppressor; and do no wrong, do no violence, to the stranger, the fatherless, nor the widow, neither shed innocent blood in this place.”

Look at the picture I snapped of the Four Species stand in my local mall and you’ll see the green etrogs, set out in rows on the display table next to special cushioning material and boxes to protect it from damage. As you read more about Sukkot and the Four Species, you’ll learn that in Jewish tradition one can try to further honor God by performing commandments with the most perfect objects possible, a concept called in Hebrew hidur mitzvah – “embellishing the commandment.” One example of this is choosing the most beautiful etrog possible. However, to keep it beautiful, it has to be kept closed most of the time, nestled in its cushioning inside a sometimes very elaborate box, taking it out only for the blessing or brief display. But remembering the sages’ comparison of the etrog to the human heart, let our “etrog” out of the box, to feel and see the invisible, especially “the stranger” is the way to more powerfully pursue justice and righteousness in our society.

Etrog, anyone? You can find out more about etrogs (not actually very tasty unless you make jam out of them) on pp. 48-49 of my book Food at the Time of the Bible: From Adam’s Apple to the Last Supper.