The Man with Four Birthdays

The man I married 40 years ago January has four birthdays.

Though he was the first child born to parents who lost almost everyone and everything in the Holocaust, it turns out that the first breath he took in this world, at Meir Hospital in Kfar Saba, Israel, may not have been his most momentous one. I missed that first birthday, obviously.

I also missed the second birthday. That was when an Egyptian artillery shell struck the convoy he was accompanying to reach Israeli soldiers stranded at the Suez Canal in the opening days of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The soldier standing right next to Arik when the shell struck was killed instantly. Then his horrified comrades saw Arik lying at the bottom of the huge crater the shell had gouged into the Sinai sand. Also dead, they thought.

Peering into the smoking pit, Arik’s comrades caught a slight movement. That must have been the moment when he felt his spine snap like a tightly stretched violin string, Arik later told me. Finding that he could hardly breathe, he willed himself to remain conscious, and it was only by forcing his back against the stretcher as the armored troop carrier bounced along the rutty road to the forward field hospital, that he survived those first few hours. It’s the same will to survive that I’ve marveled at every day I’ve known him. And it’s what he calls the battle after the war.

His shattered lungs eventually healed enough for him to survive but, added to childhood asthma, the shrapnel still embedded in them meant that when he asked for a medical permit for a scuba diving course, years after his injury, the doctor showed him the door as soon as he took a look at the file.

I wasn’t there for his third first breath either. The surgeons at the hospital in Beer Sheva had planned to operate to remove the shrapnel that had severed his spinal cord and somehow reattach it. But worn to the quick after treating many hundreds of wounded soldiers and minus senior staff that had been called to the front, the doctors made a bad decision about anesthesia and Arik suffered cardiac arrest on the operating table before they could even make the incision. They resuscitated him, and after 36 hours in a coma, he took his first conscious breath. To this day he is a D10–11 paraplegic; the designation indicates the vertebrae where the spine was severed, telling the experts what still works and what doesn’t. What did it mean for Arik?

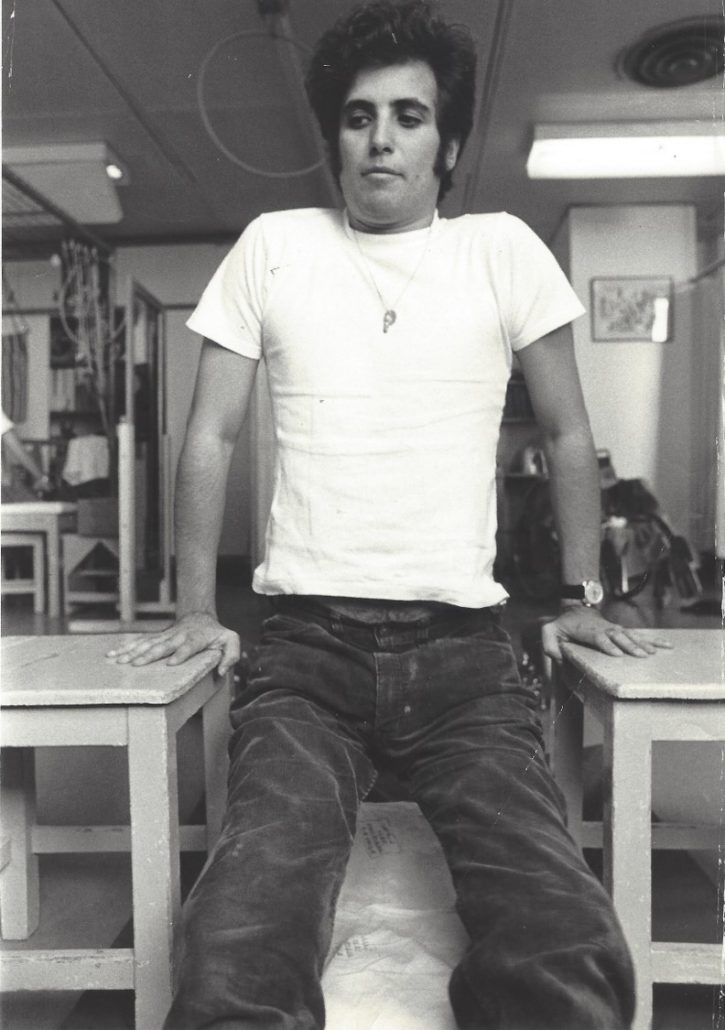

If he survived, he would be what they used to call “a vegetable” and bedridden for life, Arik’s doctors told his parents. The Arik that was born that time was the one I was to fall in love with, about seven years later. After 10 months in the hospital, grueling physiotherapy and a safari in South Africa – the first time, but not the last, that Arik would confound the experts – he returned to Hebrew University in Jerusalem to try to pick up his geology and geography studies. People close to him, friends and family, never left him for a moment. But among strangers, on campus, no one gave much thought to a man who was six feet tall and suddenly couldn’t see over an office countertop, or one who had loved to hike and now found a flight of stairs to be an insurmountable obstacle. Among strangers, even professionals, few thought about – or even knew about – PTSD. If you survived, even in a wheelchair, you didn’t need a psychologist. That’s what they figured.

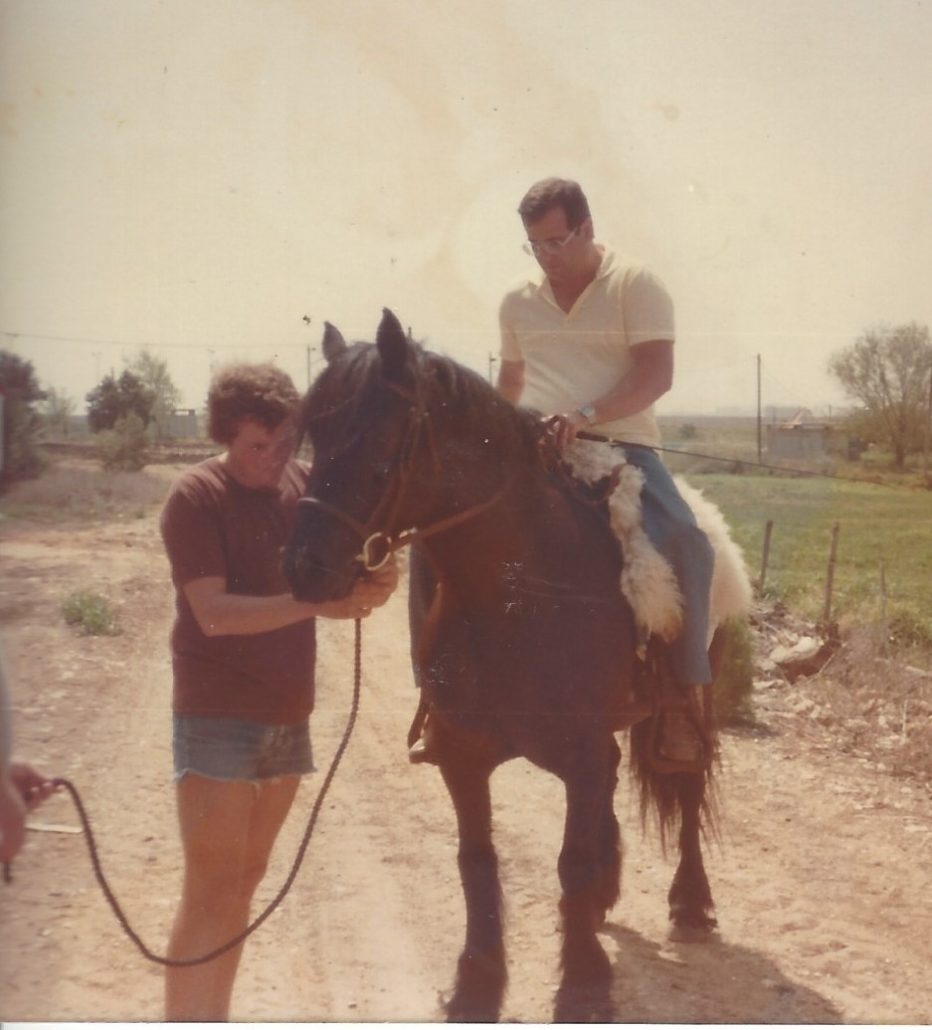

And so Arik dropped out. But since he never met a brick wall he didn’t want to butt his head against, his next move was to apply to join the Israel Police. At first, predictably, they said no. Arik would never be able to meet one of their most important entrance requirements, dating from the days when the Turks ruled the country: He had to be able to ride a horse. But he never gave up, and eventually became the first wheelchair-bound officer in the Israel Police, and, with the rank of inspector, wrote training manuals for the bomb squad and helped train the sappers in the field.

Our paths never crossed at Hebrew U, although I had stumbled through a few years on campus at the same time he was there, before I dropped out to go to tour guide school. I would have remembered him. Because when I caught a glimpse of him for the first time, wheeling through a grocery store aisle, I thought in passing, Wow, he’s cute. I don’t think I actually noticed the wheelchair. We were introduced on September 1, 1980, by Arik’s best friend, Nathan, one of my classmates in tour guide school. Four months later, we got married.

We began our married life with Arik returning to university – at Northeastern University in Boston, no less (Arik wanted an adventure). We traveled some in the U.S., but it was only years after we returned to Israel, with two college degrees, a baby and a Siberian Husky puppy, that I realized the true extent of Arik’s wanderlust.

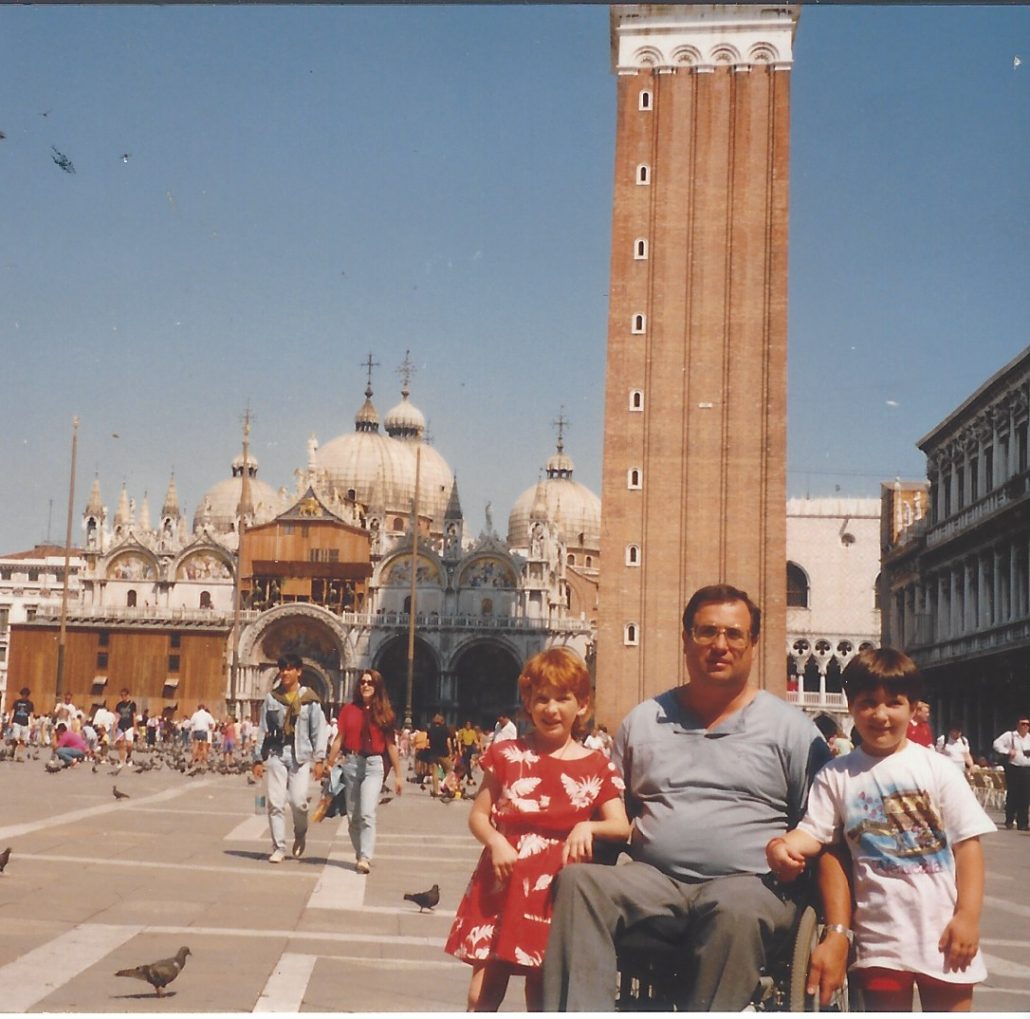

In 1990, we decided to take a camping trip through Europe with Maya, 8, and Nili, 6. It was the last thing we could afford, but Nathan, the friend who had introduced us, had just been killed, shot by accident by another soldier playing with a weapon. Several of our mutual friends, we discovered, were also taking their children on family trips, after that tragedy. On our three-week, 6,000-kilometer journey through Greece, France, Italy and Switzerland, we pitched our tent every night in a different campsite, snuggled in our sleeping bags, and every fourth day we splurged on a motel so Arik could have a normal bed and bathroom.

Then there were four trips on the wheelchair-accessible tall ship the Lord Nelson – Arik first went alone, once to the North Sea and then to the Canary Islands, plus a trip with each of the girls when they turned 16.

Were two children enough? When I suggested it was time for number three, Arik said: “Easy for you to say; you give birth, but I have to raise them.” Well, this much is true: For years, Arik brought those girls up as I gallivanted around Israel working as a tour guide. While I was away for days at a time, he did everything for them. He cooked their breakfast and dinner, drove them to preschool and picked them up, and like most Israeli parents, took them along with him to work sometimes.

As for being married to a man with four birthdays, the preoccupations of any family – mortgage payments, careers, childcare and, in Israel, intermittent spasms of terror and war – almost never fazed him. Whatever the crisis was, his demeanor (rarely his words) would suggest it could have been worse. “Well, excuse me for being upset,” I would sometimes say. “Just remember that I haven’t been through clinical death.”

As time went on, Arik mastered horseback riding, parasailing, archery and canoeing. Betwixt and between, he also traveled to St. Petersburg, where he passed a course to become the first wheelchair-bound archery judge in the world. He was a judge at the Paralympics in Atlanta, Sydney and Athens, and other contests over the years took him to Poland, Belgium, France, and Italy.

He eventually also earned his travel agent’s license, and led groups of wheelchair travelers all over the world. But he also did a lot of his traveling alone, loving the challenge of succeeding despite everything. Somewhere along the line I realized that it was when traveling the world that Arik really came alive. It was a tonic that revived him physically and emotionally, more so than any of the dozens of medications he takes just to keep going.

These were moments I no longer wanted to miss, and so I began to join him whenever I could. To Greece, Spain, Kenya, Portugal, Ireland, Britain, Cambodia, and Norway and multiple times to Thailand, culminating with a trip with all the kids and the grands, to celebrate his 70th birthday – last year, returning just as the pandemic hit.

But back to the birthdays, specifically, the fourth of his birthdays: That one, I was there for. On May 10, 2014, we entered a long, dark tunnel, after a careless young driver rammed head-on into our car on a curve as Arik was taking his mom home after lunch at our house. In the aftermath, we found ourselves clinging desperately to the tunnel walls with every light in the distance presaging another oncoming train.

At some point around the end of Month 14 post-accident, things began to look particularly bleak for me, the caregiver-spouse, what with the daily bandaging, grandmother stuff, cooking and serving three meals a day, plus a full-time job (thankfully, by then I had changed professions and was able to work from home). Even with the help of Lea, the incomparable caregiver the Israeli government provides Arik as a wounded warrior, some days it seemed like too much. Our family doctor referred me for a talk with our community social worker. “This is your new normal. You have to make a new contract,” she said. And that’s what we did. It doesn’t have to be written out or even spoken. But it has been the goal, one we continue to reach and strive to exceed with each passing day.

With the pandemic, we’ve entered a new period together. The man with four birthdays has been strangely calm. He has kept it together, and I know he’s doing it for me. You can’t be married to a man with four birthdays and live most of your adult life in Israel – or anywhere, I suppose – and expect not to come out with a heart condition; at my stage in life you can’t even expect not to lose an older sister to a heart condition. So Arik is protective of me. One time, I saw out of the corner of my right eye a prism of color, like a comic-book lightning bolt. I described it to my multiple-birthday man and told him I thought I might be having a stroke, adding that it had passed after a couple of minutes. “You probably had a tear caught in the corner of your eye and you were seeing things through the prism of light it created.” Whaaa? “Is that a thing?” “I don’t know,” he responded. And then we laughed.

It wouldn’t be the first time, in our 40 years together, that I’ve seen him through tears. Fortunately, more often than not they’ve been tears of laughter, not sorrow.

This blog was first published on the Times of Israel website

Outstanding blog! Thanks for sharing…