Go to the Aphid: Because the Alternatives are Galling

Go to the Aphid: Because the Alternatives are Galling

I’d like to think the Atlantic pistachio, the biblical terebinth, has something to teach us about ourselves.

Last week on my daily walk in my community of Har Adar I spotted a beautiful red-leaved tree that I had never noticed before. Captivated by the colors, I snapped a few pictures because I wanted to share with you a rare hint of fall foliage in my adopted Holy Land home. Here, fall doesn’t usually trumpet its arrival in a riotous changing of the leaves, but is much more subtle (unlike most everything else around here…).

A terebinth (Atlantic pistachio) showing off that it knows how to do autumn, down the street from my house.

Then I realized I didn’t know what kind of a tree it was! But with help from my wise friend, Yaacov Shkolnik and his botanical buddies, I found out it’s a terebinth, a.k.a. Atlantic pistachio (Pistacia atlantica).

The terebinth in the Bible

I didn’t recognize our local tree because it stands a lot taller than its bush-like relatives I point out to tour groups in the Valley of Elah (1 Sam. 17:2), where David fought Goliath (and where I explain that elah is the name of this tree in Hebrew). I also know some of this species that are a lot bigger and more powerful looking in the rare places where such trees have survived for centuries.

The “nuts” among the choice fruit of Canaan that Jacob instructed his sons to take back to Egypt (Gen. 43:11) were pistachios. And in the grisly tale of the Absalom’s death, it was from the boughs of a “great terebinth,” (alright, yes, some versions do say oak) that the prince was helplessly dangling by the hair when his father’s General Joab found him, and ran him through (2 Sam. 18: 9–15).

Reading more about this species, I found out that Atlantic pistachio seeds were unearthed in an excavation stratum going back some 9000 years in Jarmo, in northeastern Iraq, near the oil-rich, dispute-steeped region of Kirkuk. These seeds were also among seven types of edible nuts found – along with the stone tools to crack them open – at Gesher Bnot Ya’akov near the banks of the northern Jordan River, where our prehistoric ancestors apparently depended on them to enrich their diet some 780,000 years ago.*

Over the ages, the Atlantic pistachio has found many uses – the fruit produced oil used for lighting and medicine and the wood was carved into olive presses and other agricultural devices. The tree can also be used as rootstock on which true pistachios (Pistacia vera) are produced.

The God factor

God is in the terebinth tree – literally. The Hebrew name of the tree, elah, is derived from the word El – God. Elah, the feminine form of that word, means goddess and is yet more evidence of the sanctity of trees, and their association with goddess worship that the Bible mentions frequently (for example, Jer. 17:2). On that subject, for more information, I take the liberty of referring you to the chapter in my book Women at the Time of the Bible about women and worship. Those big old trees that I show people as we travel the country together usually survived because people believed them sacred and brought them their prayers.

Reading on, I learned that the Atlantic pistachio has quite an amazing symbiotic relationship with a certain kind of aphid. Now that gave me pause for thought. Proverbs says: “Go to the ant” – and I’m sure old King Solomon wouldn’t mind if I took a leaf, so to speak, from his book, so we can “go to the aphid” for some wisdom. But first, a little botany.

The fist-sized growths you see in the picture (they’re black now, but in spring they’re coral-colored and so they’re also called “coral galls”) are formed by aphids called Slavum wertheimae. These little guys create a kind of an incubator out of the leaves apparently only of this particular tree. Their young are nourished by the nutrients in the leaves and eventually emerge fat and happy from an opening in the gall.

Galls – baaaaaad. At least that’s what the goats apparently tell each other when they come to feed on Atlantic pistachio trees and catch of whiff of the aroma these galls emit. In fact, chemical analysis of these things showed that they emit quantities of stinky organic compounds called terpenes. Scientists observing foraging goats report that the animals turned up their noses at the Atlantic pistachio and went on to seek something less odiferous for lunch. That way the lowly aphids protect the tree from overgrazing.

Research has also shown that the galls release antibacterial and antifungal agents that also protect the tree, and scientists say they look forward to exploring possible agricultural and pharmaceutical value to these natural guardians.**

Thus, what at first glance we see puncturing and deforming the leaves of the terebinth – the aphids in their little gall cradles – actually defend the trees and help them thrive from season to season, century to century (if no one cuts them down).

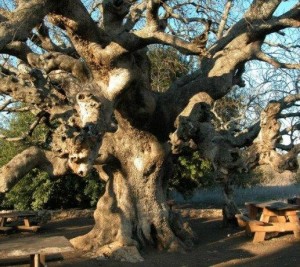

An ancient “great terebinth,” the kind people worshipped and Absalom could have hung from. Courtesy of Yaacov Shkolnik.

What the terebinth taught me

“For is a tree of the field a man…” (Deut. 20:19): Thus begins an important question Moses asked the Israelites rhetorically when instructing them not to cut down fruit trees when they besiege cities. “For is a tree of the field a man, that you make war against it?”

The Atlantic pistachio says it all: It radiates beauty, its wood is useful, its nuts nourishing, it protects itself and even hosts entities that seem poised to destroy it. No, a tree is not a “man” – “to make war against.” Humans have perfected the “art” of warfare, no doubt about that, and in our country, some are trying their best right now to rip apart a symbiosis that many believe has sustained our society for decades. And then there’s the Atlantic pistachio, which can teach us a thing or two about symbiosis and coexistence, most essentially when threats abound.

* Science Blog from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, February 2002

** “Gall Volatiles Defend Aphids Against Browsing Mammals.” M. Rostas, D. Maag, M. Ikegami and M. Inbar.www.unboundmedicine.com.

What is the terebinth tree a symbol of?

Eg. The almond is resurrection/ new life and the sycamore is the tree of repentance.

Thank you.

Beautiful question, Sue! I hope you and other readers will get some ideas from the article as to what the terebinth is symbol of to me. What do you think? As for the syamore (actually, in our country it’s syc O more, but more about that another time, I love that it’s a symbol of repentence, and you should know that it’s related to the Hebrew word shikum, which means rehabilitation – renewal. How about that for symbolism!

Loved the article and learning about one of my favorite nuts. This tree can live for 700 years! They are considered a super food and are said to be very important for eyesight as they have some of the same elements as carrots. Thanks for helping us see the biblical connection. Lucy on Maui.