A Cup of Hope on the Seder Table

A Cup of Hope on the Seder Table

As first published at Jerusalem Perspective Online

The decades have not dimmed the memory of my parents’ Seder table back in Trenton, New Jersey. It was laden with traditional family favorites, and, more importantly, with the enduring symbols of commemoration. We each had our own little bowl to hold the salt water symbolizing our tears when we were slaves. The parsley was at the ready for dipping into the salt water, symbolizing the new life and joy of our springtime festival of freedom. And of course there was the all-important Seder plate, each object representing an element of the immortal saga. The full wine cup of Elijah was there, too, waiting for the redemptive door to open. My mother added to the symbolism with her signature, green-in-honor-of-spring Passover Jello-and-pineapple ring.

Just under a week ago, in our home in the mountains of Judah, at my own family’s Passover table, we had all of those, along with a new symbol of which my mother would certainly have approved: Next to Elijah’s cup we set another goblet—brimming with water—Miriam’s cup. I’m glad my granddaughters, and the many families around the world who mark this new custom, will grow up with Miriam, sister of Aaron and Moses, “singing unto them” more powerfully than ever before.

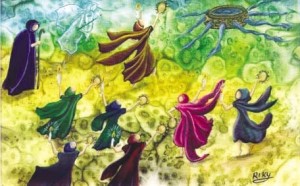

Miriam the prophetess leading praise by the seashore; facing her miraculous well as the sages pictured it. At left is Serah, daughter of Asher (Gen. 46:17; Num. 26:46), another scriptural woman who sustained the Jewish people throughout the generations, according to legend. Detail of a painting by Riky Rothenberg. Courtesy of Riki Rothenberg.

What is Miriam’s connection to water? We remember her as “prophetess, sister of Moses and Aaron,” timbrel in hand, leading the women in praise song and dance at the shores of the Red Sea (Exod. 15:20–21). But there’s much more. The medieval commentator Rashi, explaining Psalm 110:7, interpreted her name as having two parts: mar, a Hebrew word for “bitterness,” plus the Hebrew word for “sea,” yam. In fact, those are the two elements that bookend the drama of Miriam’s early life, from the bitterness of the slavery into which she was born, to the shores of the Red Sea where she emerges as a public leader, part of a team, as the prophet Micah (6:4) reminds us.

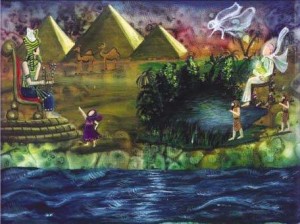

Miriam was a prophet, says Exod. 15:20—the first woman in the Bible to receive this title. The Bible does not tell us what she prophesied, but the ancient sages are there, as always, to fill in the blanks. The two midwives, Puah and Shifra (Exod. 1:15), they said, were none other than Jochebed, Miriam’s mother, and her five-year-old (!) daughter. In this imaginary telling, Pharaoh summons Miriam and Jochebed to his palace to deliver his diabolical edict—to kill the Hebrew baby boys they had delivered. The world’s most defiant toddler then stamped her foot (as I picture it) and warned the Egyptian ruler: “Woe to this man because of his evil deeds when God is finished with him.”

A fearless little Miriam tells Pharaoh off at the banks of the Nile. At right, Jochebed enthroned. Detail from a painting by Riki Rothenberg. Courtesy of Riki Rothenberg.

Further evidence of Miriam’s prophetic skills comes from the ancient commentary on Exodus, Exodus Rabbah, which teaches that when the Israelites realized Pharaoh’s plot, “many men decided to remain separate from their wives.” But young Miriam predicted: “a son will be born to my father and my mother at this time who will save the People of Israel from the hand of Egypt.” Persuaded by the sheer power of their daughter’s words, Jochebed returned to her husband Amram enthroned as a queen. She gave birth to a son, “and…the house was filled with a great light like the sun and the moon at their rising.”

Despite her leadership status, in fact, no doubt because of it, the Bible highlights an incident revealing a character flaw. Numbers 12:1-2 finds Miriam and Aaron apparently gossiping about their Cushite sister-in-law and maligning big brother Moses. Miriam bears the brunt of the punishment, struck with leprosy.

However, the same ancient sources who took Miriam to task and accused women in general of being prone to idle talk, also gave us Miriam’s most enduring, positive association, which comes to her only in death. Scripture speaks of Moses’ death and unmarked grave on Mount Nebo (Deut. 34:1-2, 6). As for Aaron, Numbers 20:29 says the whole house of Israel wept for him and mourned him for 30 days. But when it comes to the third member of the triumvirate, there is only the date, “the first month,” and the place, Kadesh (Num. 20:1).

The barren wilderness of Kadesh, where Miriam is buried, as seen from Israel’s present-day border with Egypt in the western Negev. Photo: Miriam Feinberg Vamosh.

But then, it is the very next verse that brought Miriam’s cup to our Seder table. The sages who interpreted Scripture were all about connections, and the fact that the death of Miriam is immediately followed by an assembly, not of mourning but of “striving” (Num. 20:3), was simply too good to leave alone.

In answer to the people’s outcry, God tells Moses to strike a rock, bringing water gushing forth (Num. 20:8-12). The Ethics of the Fathers speaks of this well as one of ten amazing sights created on the eve of the first Sabbath after creation—on a par with the rainbow after the great flood, manna, and Moses’ miraculous staff (Ethics of the Fathers 5, 6). In the Babylonian Talmud, Rabbi Jose noted that the well, like other miraculous gifts, was given out of merit for the three wilderness leaders (Babylonian Talmud, Taanit 9a). Because Miriam’s most memorable deeds involved water—saving Moses and leading the women in praise song and dance next to water—the people felt the lack of water most powerfully when she died. And so, in her honor, God caused the well, which had mysteriously disappeared, to return. When the head of each tribe would strike the rock, water would emerge in a stream leading to that tribe’s encampment. Wherever the tribes encamped, there the well would be.

Miriam’s well, as the sages pictured it. Detail of a painting by Riki Rothenberg. Courtesy of Riki Rothenberg.

The legend of Miriam’s well is still with us. Christian pilgrims crossing the Sea of Galilee spot many boats making the crossing with them, pausing mid-lake just like they do. But passengers on other decks are sometimes pilgrims of another faith—their dress clearly identifying them as Orthodox Jews. They are there waiting for a spring—none other than Miriam’s well, which they believe ended up here—to bubble up from the depths of the lake, as it intermittently does, as a sign of God’s faithfulness and healing power.

A 2012 film about reconnecting and renewal bears the name of the fictional town that is its backdrop: “Hope Springs.” That play on words was not accidental. Hope springs eternal, Alexander Pope said. The cleansing and quenching of our spiritual thirst, the promise of new growth nourished by winter rains of blessing in the Holy Land, are all contained in “Miriam’s cup.”

Women dance, rarely, elsewhere in the Bible (1 Sam. 18:6; Judg. 11:34; 21:21; Ps. 68:25). But it is Miriam who is depicted by the Jewish mystical text, the Zohar, as dancing in Heaven. Miriam’s dance was unique, the very embodiment of praise and hope, which continues to promise that wherever we set our Seder table, in the words of the ancients, “sustenance may be granted for the sake of one individual.”

Sister and brother: through thick and thin: My great-niece Adella (right), her arm around her little brother Cole, remind me of Miriam and Moses, and other shorelines. San Francisco, 2015. Photo: Sierra Schwidder.

Beautiful and meaningful